Pelvic mesh reforms have become a critical issue in the UK’s healthcare system, as thousands of women continue to suffer severe complications from these once widely used surgical implants. Designed to support weakened pelvic tissue and treat incontinence, pelvic mesh procedures have instead left many patients with chronic pain, disability, and psychological distress. Although the First Do No Harm report in 2020 outlined essential recommendations for reform, campaigners argue that progress on pelvic mesh reforms has been painfully slow—leaving victims without justice, compensation, or adequate medical support.

The Pelvic Mesh Reform Delay: A Devastating Medical Crisis

Calls for urgent pelvic mesh reforms have intensified in recent years, as thousands of women continue to suffer from the life-altering complications of pelvic mesh implants. In 2020, the First Do No Harm report by Baroness Julia Cumberlege exposed systemic failures in the regulation and monitoring of these implants, alongside the drugs Primodos and sodium valproate. The review featured testimonies from over 700 affected individuals, revealing widespread harm and a healthcare system slow to act.

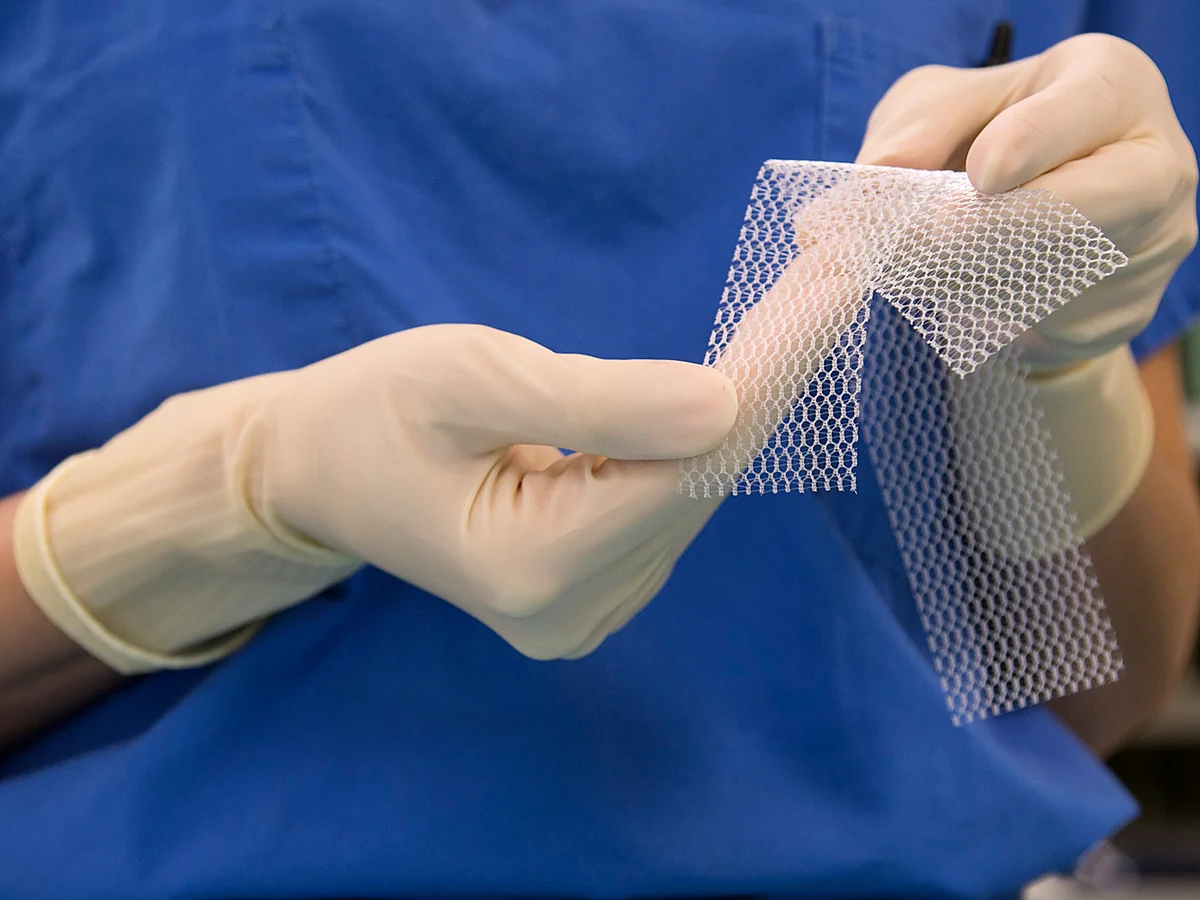

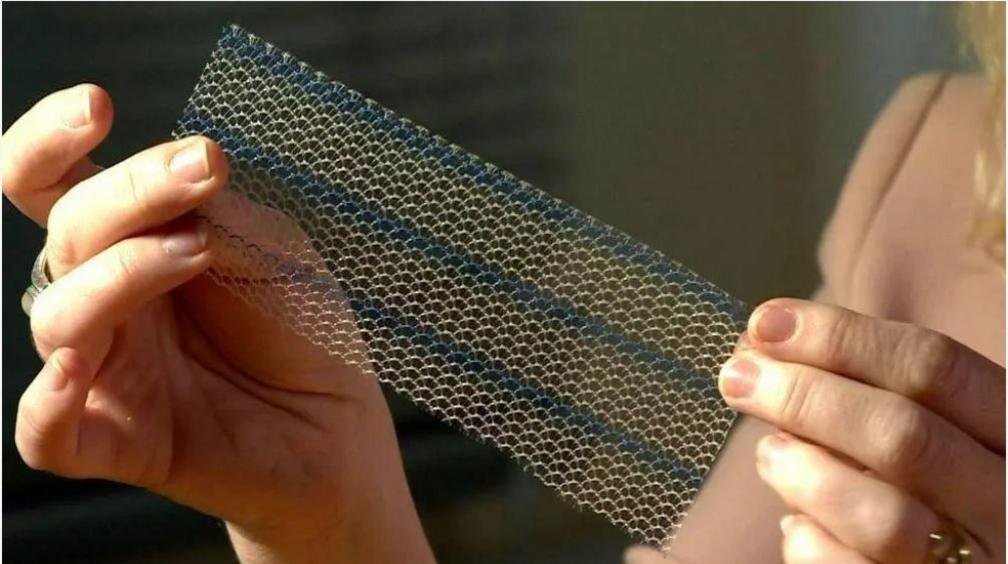

Pelvic mesh, designed as a net-like implant to support pelvic organs, often caused severe complications. The mesh could harden or erode, cutting through internal tissues and leaving women with permanent, debilitating pain. Many victims reported being unable to walk, return to work, or maintain intimate relationships.

Drugs like Primodos and sodium valproate also caused devastating outcomes. Researchers linked Primodos to birth defects and miscarriages. Sodium valproate, a medication for epilepsy, caused major birth defects when pregnant women used it. Critics argue that doctors and manufacturers failed to adequately inform patients about these risks.

From Pelvic Mesh Victim to Reform Advocate

Kath Sansom never imagined she would become a national voice for medical safety reform. After receiving a mesh implant to treat post-childbirth incontinence, she began experiencing “terrible pain” that altered her daily life. Realizing that countless other women had suffered similarly, she founded Sling The Mesh, a grassroots campaign advocating for recognition, justice, and reform.

“The pelvic mesh reform delay reflects an institutional failure to take women’s health seriously,” Sansom said. “Baroness Cumberlege’s report was a landmark in exposing medical negligence, but five years later, too many of its critical recommendations remain untouched.”

Pelvic Mesh Reform Delay: Progress and Stalemates

Authorities have fully implemented only three of the nine key recommendations from the First Do No Harm report.

- A formal government apology to victims

- Establishment of specialist centres to treat mesh complications

- Appointment of a Patient Safety Commissioner for England

Work is still underway to create a national database that tracks patients fitted with medical devices.

However, major gaps remain. Chief among them is the absence of any government-backed compensation scheme for victims. Women who trusted their doctors and followed medical advice now find themselves abandoned by the very system meant to protect them.

Political Frustration

Sharon Hodgson, Labour MP and chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on medical harm, also criticised the government’s inaction. “The pelvic mesh reform delay is deeply disappointing. Five years ago, we felt that the system would begin to listen to women. But the silence is deafening.”

She pointed out that thousands of women and children have been harmed by medical products whose risks were underestimated or ignored. “These families deserve compensation and a commitment to reform—not bureaucratic stalling.”

Shifting the Safety Role

One major concern voiced by campaigners is the recent decision to move the role of the Patient Safety Commissioner from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Sansom sees this as a move that weakens accountability.

“Transferring the commissioner to MHRA undermines the independence of the patient voice,” she said. “It feels like an attempt to dilute advocacy rather than strengthen it.”

Government Response

A spokesperson for the DHSC acknowledged that the effects of pelvic mesh harm are still being felt today and expressed sympathy for affected women. “The Department of Health is carefully considering all the recommendations and will provide a full update.”

Health Minister Baroness Gillian Merron reportedly met with victims and has promised further engagement. However, critics argue that sympathy must be matched with action.

The Call for Compensation and Reform

Campaigners are urging the government to prioritize:

- Financial compensation for victims

- Faster rollout of a national patient-tracking system

- A statutory duty for listening to patient complaints

- Continued investment in specialised treatment centres

- Independent regulation of patient safety roles

Until these demands are met, advocates like Kath Sansom say that women harmed by pelvic mesh will continue to suffer in silence.

“This isn’t just about pelvic mesh,” she said. “It’s about how the system treats women’s health and whether it takes responsibility for the harm it has caused.”

Conclusion

The pelvic mesh reform delay is a stark reminder of the challenges facing women in securing justice for medical harm. Five years after a landmark report, only limited progress has been made. Campaigners continue to call for full implementation of safety reforms, meaningful compensation, and a healthcare system that truly listens to its patients.