Harvesting Venom: How Australia’s Deadliest Animals Save Lives

Australia’s deadliest animals play a surprising role in saving lives through a vital antivenom program. At the Australian Reptile Park, Emma Teni carefully coaxes a large Sydney funnel-web spider into a defensive stance. Using a tiny pipette, she extracts venom from its fangs—an essential step in producing effective antivenoms.

This groundbreaking program relies on venom from spiders, snakes, and other toxic species. Despite their fearsome reputation, Australia’s deadliest animals provide critical ingredients that support a nationally and globally recognized lifesaving initiative.

This important program relies on venom from spiders, snakes, and other dangerous species. Despite their fearsome reputation, Australia’s venomous animals provide vital components for a globally recognized antivenom initiative.

Spider Venom from Australia’s Deadliest Animals: A Deadly Bite with Healing Potential

Experts rank Sydney funnel-web spiders among the most dangerous spiders in the world. One bite can be fatal within 15 minutes, yet since the antivenom programme began in 1981, there have been no deaths.

Emma, known by some as “Spider Girl,” milks venom from up to 80 spiders a day. The park relies on public donations—citizens carefully capturing these creatures and submitting them to collection points, such as vet clinics.

“These spiders, though deadly, become heroes once milked,” says Emma. “Thanks to people who catch and hand them in, we can produce antivenom and save lives.”

Male funnel-webs are particularly valuable, being significantly more toxic than females. Staff milk the male spiders every two weeks after sorting them. It takes venom from around 200 spiders to create just one vial of antivenom.

From Venom to Vial: The Journey of Antivenom from Australia’s Deadliest Animals

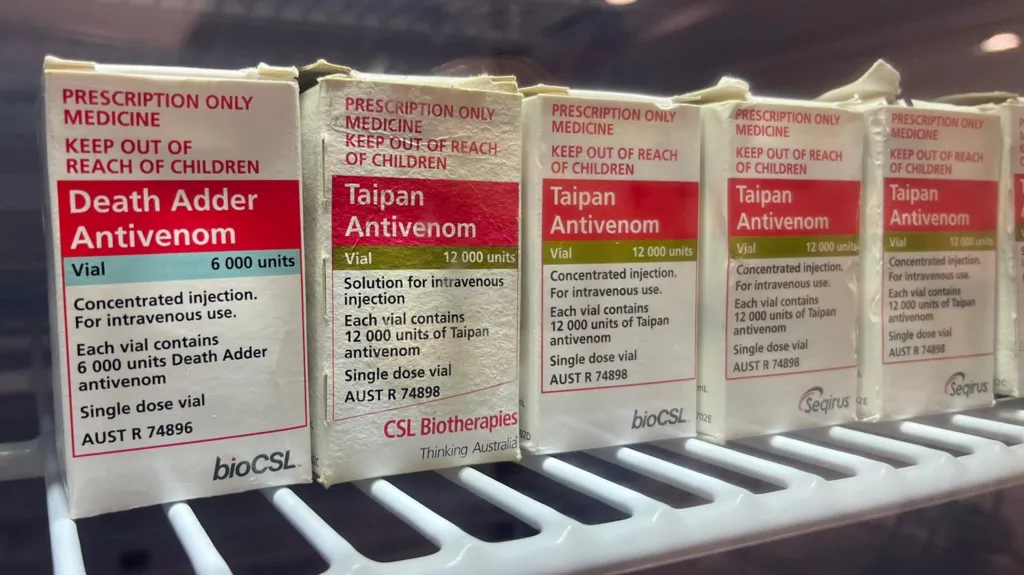

CSL Seqirus in Melbourne receives the extracted venom and begins a complex antivenom production process. Scientists inject rabbits with controlled doses of spider venom to stimulate antibody production. They then extract the antibodies from the rabbits’ plasma and refine them into life-saving antivenom.

Snake venom follows a similar process, with horses used instead due to their size and immune resilience. The final product, once packaged, can take up to 18 months to prepare and is valid for three years.

Snakes: Silent Saviors in Australia’s Bushland

At the same park, Billy Collett, operations manager, milks snakes like the King Brown—one of Australia’s most venomous species. Handling them without gloves, he collects venom as it drips into shot glasses covered in cling film.

“That venom could kill everyone in the room multiple times over,” Collett says. “But they don’t want to bite humans. Bites usually happen when someone tries to kill or handle them.”

Technicians meticulously label each snake antivenom vial—“Taipan,” “Tiger Snake,” “Eastern Brown”—before freeze-drying and processing the venom for emergency medical use.

Australia’s Lifesaving Antivenom System

Australia’s antivenom programme is renowned globally. While WHO reports up to 140,000 snakebite deaths worldwide each year, Australia records only one to four annually, thanks to early intervention and readily available antivenom.

CSL Seqirus manufactures 7,000 vials of antivenom annually and strategically distributes them across Australia. The Royal Flying Doctor Service, navy vessels, and even remote clinics all receive tailored supplies based on local wildlife.

Beyond Borders: Antivenom Diplomacy in Papua New Guinea

Australia also sends 600 vials annually to Papua New Guinea, a country still facing high death rates from snakebites. The initiative, described by some as “venom diplomacy,” underscores Australia’s commitment to regional health.

“In some ways, our antivenom has more impact in Papua New Guinea than here,” says Chris Larkin of CSL Seqirus. So far, their donations have saved over 2,000 lives abroad.

Fear Meets Fascination: Changing Public Perception

Despite the inherent dangers, Emma and Billy work to shift the narrative around venomous creatures. “They’re not monsters,” Emma says. “They’re crucial to medicine. With respect and caution, they’re helping us survive nature’s deadliest encounters.”

Billy adds with a smile, “If you’re going to be bitten by a venomous snake, Australia’s the best place for it—we’ve got the best antivenom in the world.”