Abu Abraham: The Political Cartoonist Who Fought Censorship

Born in 1924 in Kerala, Abu Abraham became one of India’s most influential political cartoonists — a cartoonist who fought censorship with wit and conviction. Through sharp satire, he boldly challenged authority, especially during the Emergency in India. He began his journalism career at the nationalist Bombay Chronicle, where he developed a deep fascination with politics and the power of the printed word. His early experiences witnessing India’s independence deeply shaped his voice as a cartoonist committed to truth and dissent.

After working briefly at Shankar’s Weekly, Abu Abraham—the political cartoonist who would later be known as a cartoonist who fought censorship—set his sights on Europe. In 1953, a chance encounter with British cartoonist Fred Joss paved the way for his journey to London. Just a week after arriving, one of his cartoons was published in Punch, earning praise from editor Malcolm Muggeridge, who called it “charming.”

Soon, Abu’s work appeared in Tribune, attracting the attention of David Astor, editor of The Observer. The editor offered him a staff position and suggested he adopt the pen name “Abu” to prevent misinterpretation of his surname in Europe.Astor guaranteed him full creative freedom—a rarity in the world of political commentary.

How the Cartoonist Who Fought Censorship Rose in British Media

Abu Abraham, a renowned political cartoonist, spent ten years at The Observer and three at The Guardian before returning to India. Widely respected for his empathetic satire, Abu Abraham was a cartoonist who fought censorship — especially during the Emergency in India. His fearless illustrations defined the phrase “Abu Abraham political cartoonist Emergency India” among admirers of press freedom. David Astor once told him, “You are not cruel like other cartoonists.” That remark captured Abu’s humanistic style and lasting legacy.

While he achieved considerable success in Britain, Abu grew weary of British politics. By the late 1960s, he returned to India, joining The Indian Express as a political cartoonist. His return coincided with a politically volatile period in India.

The Emergency: A Battle for Expression

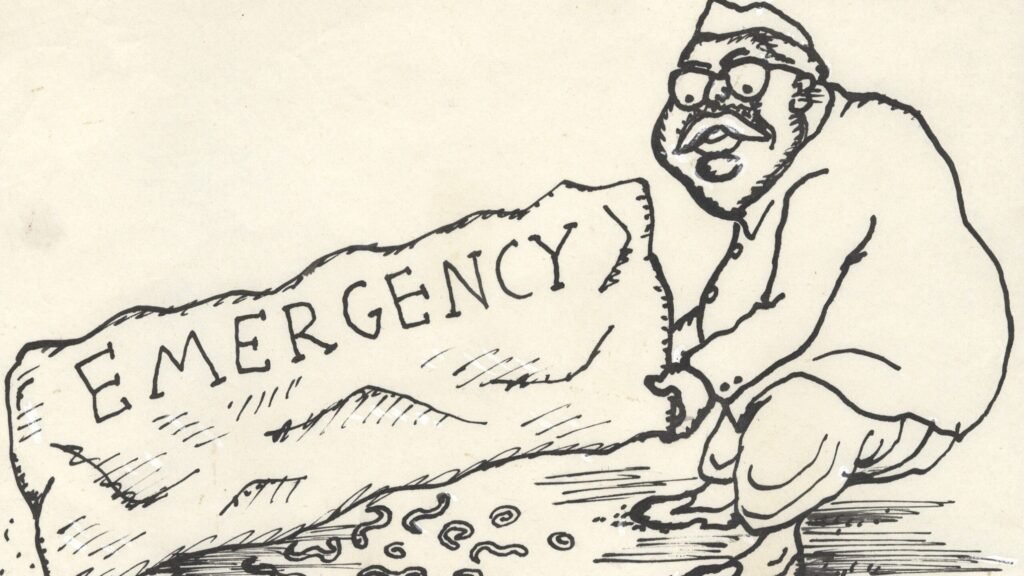

On 25 June 1975, the Indian government under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of Emergency, marking one of the darkest periods for press freedom in India. As censorship laws took effect overnight, Abu Abraham, the fearless political cartoonist, rose to prominence for his satirical critiques. During the Emergency in India, Abu Abraham emerged as a bold voice of dissent against silenced media and shrinking civil liberties.

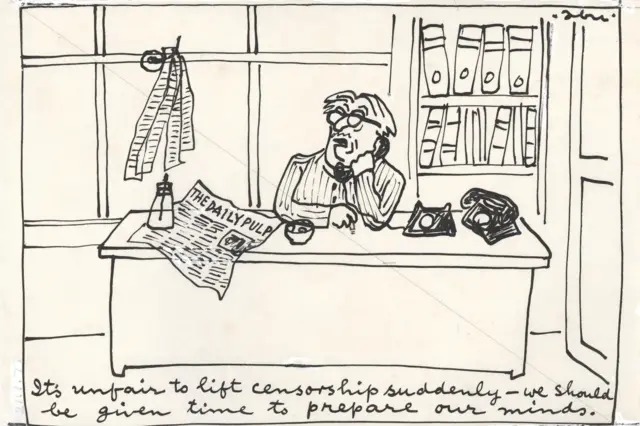

Abu, already established as a leading voice in political satire, used his pen to critique the authoritarian measures. One of his iconic cartoons shows a grizzled editor grumbling over the phone: “It’s unfair to lift censorship suddenly. We should be given time to prepare our minds.” The irony struck deep.

Another memorable cartoon featured two characters: one asks, “What do you think of editors more loyal than the censor?” Abu’s wit and incisive visual commentary challenged the fear and silence gripping the press.

Satire as Resistance: How a Cartoonist Fought Censorship

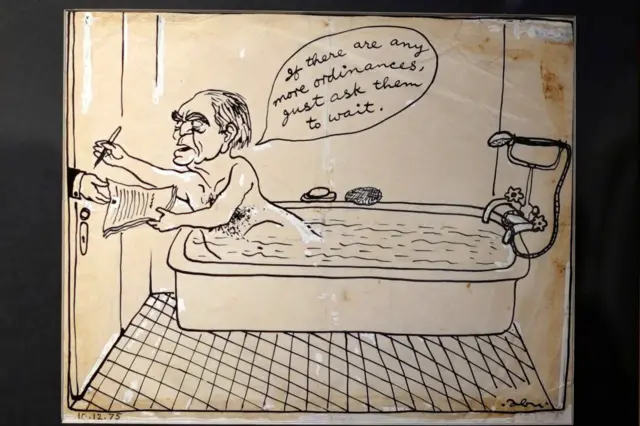

Abu’s cartoons during the Emergency era were bold. One unforgettable cartoon showed then-President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signing the Emergency proclamation from his bathtub. It captured both the absurdity and the haste of that decision.

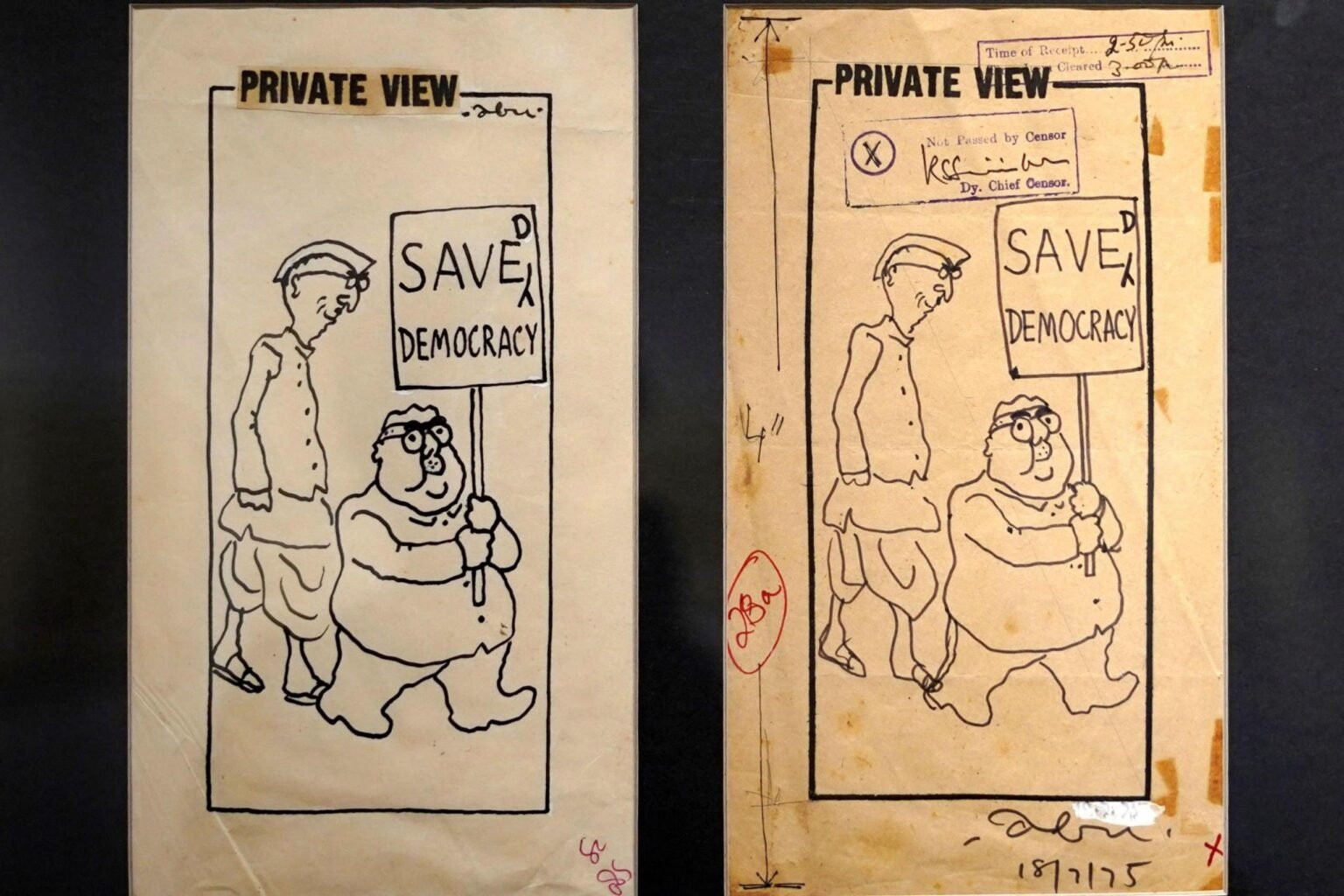

He often stamped his works with a defiant note: “Not passed by censors.” Another cartoon jabbed at the government’s forced positivity campaigns, with a placard that read “Smile!” and a character remarking, “Don’t you think we have a lovely censor of humour?”

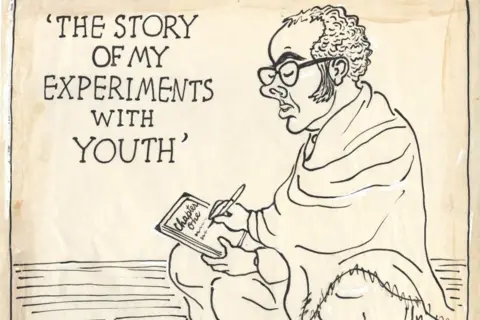

Abu didn’t shy away from critiquing Sanjay Gandhi either—the unelected son of Indira Gandhi, whose unofficial authority sparked both fear and resentment. Despite looming threats, Abu’s cartoons continued to be published, many questioning the shrinking space for democracy.

Beyond Cartoons: Political Commentary and Parliament

Abu viewed the world as inherently political. In a 1976 essay for Seminar magazine, he wrote, “Politics is simply anything that is controversial—and everything is controversial.” He lamented how dull newspapers had become, filled with praise and stripped of critique.

In one column, he mocked the wave of political sycophancy with a fictional account of the “All India Sycophantic Society,” where the motto was, “Servility before self.” The parody ended with the declaration: “Touching all available feet and promoting a broad-based programme of flattery.”

His commentary was as cutting in print as it was on paper.

From 1972 to 1978, Abu served as a nominated member of India’s Rajya Sabha. He used the role to champion artistic freedom and responsible journalism.

Returning Home: Kerala and the Comic Strip Era

In 1981, Abu launched a comic strip called Salt and Pepper. It ran for nearly two decades, combining social commentary with everyday Indian life. It showcased his versatility—he could go from biting political critique to gentle, relatable humor.

He returned to Kerala in 1988 and remained active as a writer and artist until his death in 2002. Even in his later years, Abu continued to reflect on the state of media, censorship, and the power of satire.

A Legacy Etched in Ink

Abu Abraham’s legacy goes far beyond the cartoons themselves. He once remarked, “If anyone has noticed a decline in laughter, it may not be due to fear of mocking authority, but because reality and fantasy, tragedy and comedy, have all somehow become blurred.”

That mixture gave his work its lasting power—holding up a mirror to society, often absurd, occasionally tragic, but always honest.

In a moment of sharp irony, he wrote, “The prize for the joke of the year should go to the Indian news agency reporter who praised a British newspaper’s comment that ‘trains are running on time’—not realizing it was once a classic joke about Mussolini’s Italy.” When we have such innocents abroad, we don’t really need humorists.”

His pen never wavered, even as others chose silence. Through his fearless work, Abu Abraham became one of India’s most courageous and influential voices against censorship and conformity.